Live with the refugees, don’t only listen to their stories

A journey with Bahraini volunteer Aisha

It was 3:00 am when Sham, eight years old, arrived at the Hungarian border. The girl was unable to talk anymore after a terrible scene she has witnessed.

The details of the story were heard by the Bahraini volunteer Aisha Al-Sharbati from Sham’s grandfather and she promised to narrate to the whole world.

It is a story no like any other stories which she met and lived during her journey that has started 7 years ago with the refugees and migrants.

In this journey, we are guided by the Bahrain young lady to some of its key stops.

Let us uncover the stories of those fleeing wars, disasters, and famines.

Child Sham– the first stop in our journey

The girl with the yellow coat

October 15, 2015

“I will never forget this date of October 15, 2015,” says Aisha.

The very same scene was repeated every day that year: in the early hours of dawn, a group of refugees fleeing wars in their countries, especially Syria, would arrive at the Austrian border in the company of a Hungarian man.

It was cold and the scene was getting harsher by the pale faces of the cold weather as they came out of the trees after walking long distances through the harsh forests of Austria.

Aisha was one of the volunteers working with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). She receives the refugees crossing the forest with blankets and foods until they are transported to a safe refugee center on the borders. In 2015, the UNHCR recorded 4.5 million people were displaced from their country.

This day was going to pass like any other day with some painful stories making it difficult for the young Bahraini lady to get to sleep until she saw the girl with the yellow coat.

The Syrian child Sham

“Her little body was shaking from cold weather. Her grandfather, a very old man, was holding her hand. He was looking around as if he wanted to scream or speak out,” Aisha told Tiny Hand.

The man felt very happy to find out that Aisha speaks Arabic. He told her all details of the death journey which he, his daughter, and his granddaughter Sham had made.

Aisha recalled, “It was the most beautiful child I have seen in my life. In her eyes, I could see her pains and the pains of Damascus, the city after which the girl was named and from which she was displaced.

Here is a full account of what happened to Sham as narrated by Aisha in the video:

But what brought Aisha, the young Bahraini lady, to these borders?

Aisha

Aisha

with news about Syrians and the major immigration waves taking place in the country.

In the beginning, she started to express her thoughts on social media, but she reached a moment when she felt that this was not enough and that what she writes will not help that Syrian person stuck on the borders fleeing the war in his/her country.

“At this moment, I decided to start my volunteering journey to help the refugees through translation and legal consultations, especially that I have studied law. In addition, I would provide in-kind and financial support as well as any service that would facilitate the asylum journey a refugee is making,” Aisha explained.

It seems that all that started with her choice to pursue her university study in the field of law, which was against the wish of her family that encouraged her to study medicine. Aisha noted, “I wanted to explore the intricacies within the human soul and feel man’s sufferings rather than only perform a surgery to a person and then s/he goes back home and it is over.” She added, “It is a nice decision and I will never regret it.’

After graduating from university, she worked as a volunteer lawyer taking cases of Bdoon (undocumented residents), domestic workers, victims of domestic violence, harassment of women, and their rights.

Besides, she received training at the UNHCR, where she worked for three years with refugees coming from the Arab region, especially Syria. In 2017, Aisha started a new journey that took her to Bangladesh where she met Muhammed Radwan, a young boy fleeing the massacres taking place in Myanmar.

Muhammed Radwan’s miserable journey to get outside Myanmar

In a makeshift hut made of bamboo and covered with plastic cloth, Muhammad Radwan, seven years old, was packing his school items in a small plastic bag while a lamp swung over his head. He was standing on a mat on which he and his family sleep.

.

Radwan does not know what brought him there in a shelter located at a distance less than two thousand kilometers from his home in Arakan state, western Myanmar.

He was four years old when his family fled the massacres committed by the Myanmar army against the Rohingya minorities.

Radwan, whom Aisha interviewed at the temporary education center in Cox’s Bazar camp, was the closest to her heart, as he was “a polite and tactful child who would quarrel with his friends whenever they tried to cause troubles and riots in the early education center," according to Aisha.

He would politely tell them, “We have to show respect for people.”

Although Aisha’s knowledge of the Rohingya language does not exceed a few words such as what means “You are beautiful, you are handsome, laugh, etc.” However, with the help of an English interpreter, she was able to create a world for herself inside the largest camp in the world, which she would not be able to leave later; helping them has become an important part of her life.

Among the refugee children was child Muhammed Radwan. He is one of the hundreds of thousands of children who live there. “Most of them are naked, barefoot, born without a nationality, and they grow up without education. If they receive any education at all, it is often limited to the alphabet and simple math problems. They go through life without goals and fear that they leave it without anyone hearing about them as happened with the refugees of the older generation who came to the camp 30 years ago in the first wave of Rohingya minorities displacement,” Aisha added.

About 919,000 Rohingya refugees now live in southern Bangladesh. The vast majority of them live in camps and settlements that have emerged in Cox’s Bazar region, close to the border with Myanmar

Today, Aisha has not heard anything about Muhammed Radwan for more than a month after the Bangladeshi government decided to close the camp and prevent visits to it amid the Coronavirus pandemic.

We asked her to talk more about his daily routine. Aisha said, “Like other camp’s children, Muhammad Radwan wakes up with the sunrise, line up in long lines to get food, and then start playing with other kids.”

The children turn anything that falls in their hands into a toy; Aisha explained, “These kids are very smart and the amazing entertainment staff and toys they make with their own hands prove it. It is a good thing that helps them overcome the sufferings they are going through.”

Mohamed Radwan is considered the most fortunate of older children. Informal education in the camp is only permitted for children between 4 and 12 years.

And as soon as the sun begins to set, this camp turns into another world, Muhammad Radwan and all other children go back to their tents for sleep to start their same routine the next day.

They hang their hopes on their country, which they cannot return to because the international law prevents them as the threat to their lives is still there.

Now, what is Aisha’s journey?

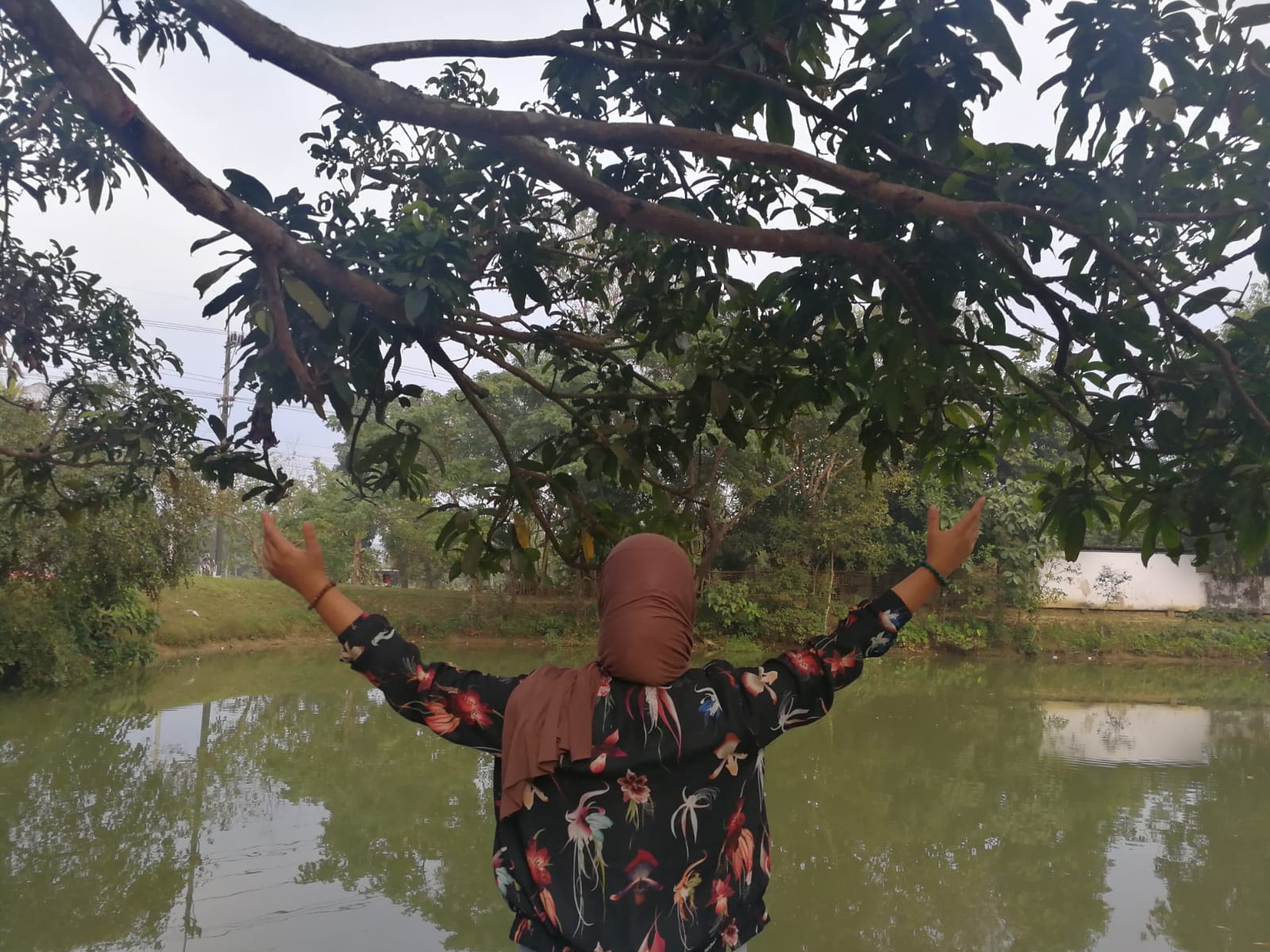

On the last stop with Aisha, before we bid her farewell in the capital city of Dhaka, we asked her some questions so she could summarize her journey of volunteerism.

What is your wish?

To shed more light on refugee women, especially in Rohingya refugee camps. For example, the average time a woman is allowed to have outside her tent is only 30 to 40 minutes a day, and that is either to go to the bathroom or to see a doctor. The local community does not allow her to mix with others.

Through my work with them, I discovered that women do not have the opportunity to express themselves and release their emotions. Women suffer greatly from the lack of sanitary pads that are not provided for them.

On one occasion, we asked more than 800 women in the camp about the most thing they wanted to get, the answer of 600 of them was a “mirror” so that they could see their faces.

From your experience working at Cox’s Bazar camp, what is the solution to the refugee problem?

There is no enough life experience to solve this issue, but let’s hope for the best for them.

How do you fund your volunteer trips?

I make them at my own expense. For some trips, I am fortunate to have donators but they usually only finance one trip. Anyone accompanying me on any trip is often at their own expense too.

What is the most significant achievement you are proud of?

My project with the refugees and volunteering to help others using our creative ideas, especially for the women’s community.

They have sensitive matters that we must take care of.

One of the beautiful things was that I had a role in changing the lives of many refugees. Indeed, this is an achievement that makes me proud

What is the most important thing you learned from all this experience?

I learned that there is nothing in this world of value; everything will disappear and things change overnight. Therefore, we should not postpone anything and the right time for doing anything is this moment. What we need most today is “kindness in treating others, tolerance, and acceptance.”

Finally, what is your message for refugee children? How can they pursue their dreams and work to achieve them while they are in these conditions?

Refugee children face very difficult situations. In my view, they have been able to overcome them. So anything else will be easy for them to do, especially since most of the creative people in our life are those who have experienced a lot of suffering. Therefore, I am sure that these sufferings will bring out the best in them.