I was and I became

Tiny Hands, Heavy Burdens: A Child's Life on the Construction Site

At five in the morning, we met Issa in his modest, rural home in al-Karamah area of the Raqqa countryside. The early breeze bit into our faces as Issa finished breakfast with his brothers and father. Dressed in a red shirt, he had pulled on a light cotton jacket to shield himself from the morning chill.

“Are you tired?” his father asked, glancing at him with concern.

Despite the clear signs of exhaustion on his face, Issa offered a shy smile and shook his head. His father asked again, “Are you tired? If you’re feeling worn out, you can stay home today.” Issa replied, “Yes, I feel tired, but I’ll still go to work.”

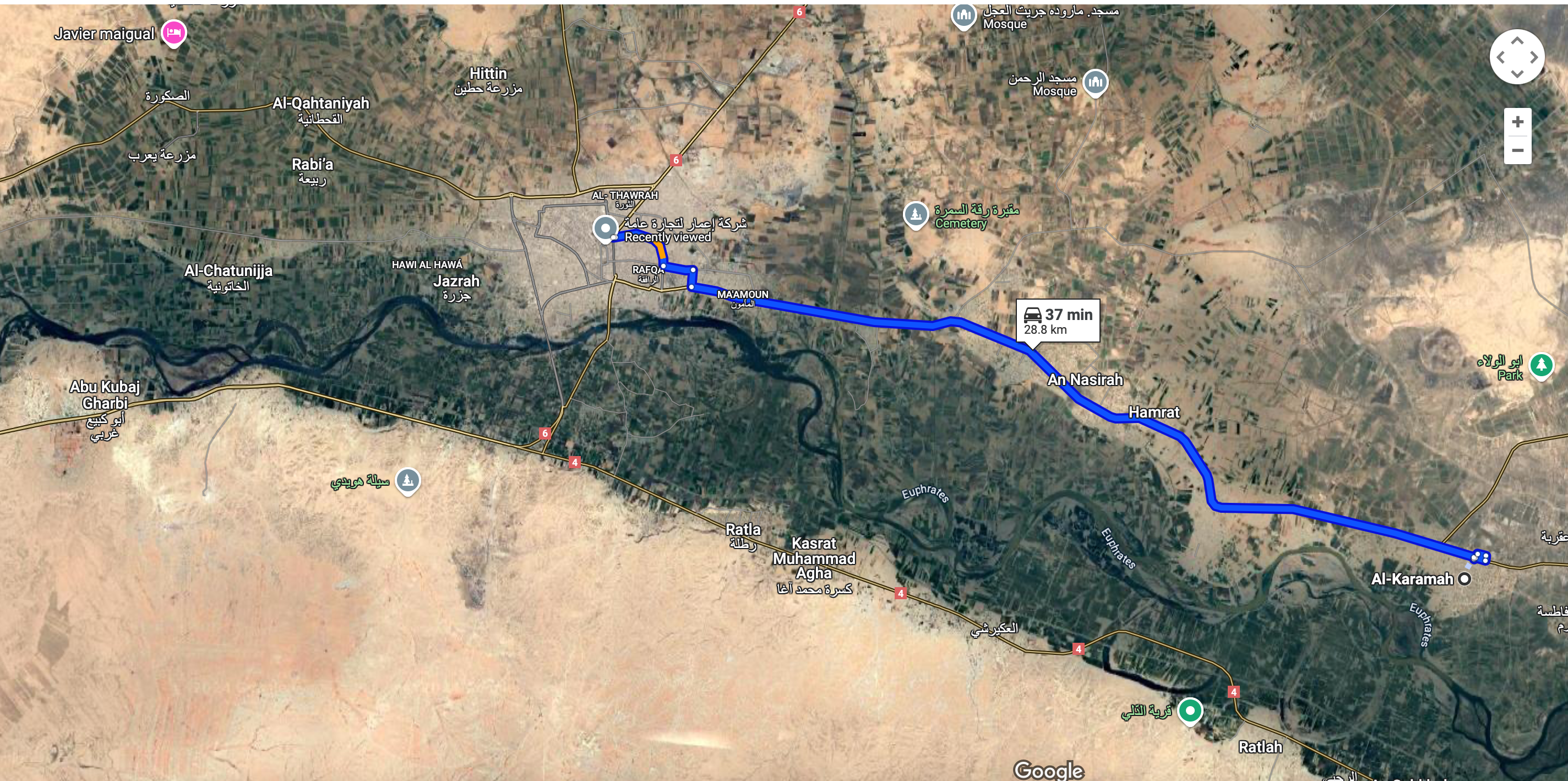

We set off toward the work site with Issa, the youngest of his three brothers, and his father driving the pickup truck. We moved through the village, picking up workers his father had previously arranged to transport to Raqqa, a city about 29 kilometers away, or roughly a half-hour drive.

The distance that Issa travels daily from his home to the workplace.

The distance that Issa travels daily from his home to the workplace.

Issa shivered in the cold, his eyes fixed on the road as he waited for his father to stop and pick up the other workers. He knew that once everyone was on board, he’d feel warmer. “This tarp —the cloth covering the back of the truck—helps block out the cold a little, but once everyone’s in, it’ll warm up here. We’ll huddle together to stay warm," he told us.

The child, who began working at just ten years old, has no connection to school, having attended only two years. When we asked him, “Do you miss going back to school?” he shook his head and said, “When I see other kids going to school, I don’t feel any urge. I don’t want school; I don’t like books or bags.”

In Raqqa, northeastern Syria, children continue to live amid the rubble, with scarce access to water, electricity, and education—years after the city was reclaimed from ISIS in 2017. Since the battle ended, thousands of people have either returned or relocated to Raqqa, with an estimated 270,000 to 330,000 residents now living there. Despite these resettlements, the conflict in Syria endures, nearing its 14th year.

At the work: Hands that tell the whole story

At the construction site we arrived at in a neighborhood of Raqqa, about six children were present. The oldest among them was no more than sixteen, while Issa was the youngest.

It appeared they were in the final stages of the construction project. We spent the day on the roof of the building with them as they cut, measured, and stacked the iron.

They work long hours in challenging conditions, climbing multiple floors while carrying iron. The toll of this labor is evident on Issa’s hands, which are blackened and cracked from the work he began at the age of ten.

Iron instills a sense of terror in this child's heart, particularly when he has to carry it from the lower floors to the upper ones. He must grip it tightly and maintain his balance to prevent it from falling and pulling him down with it. He explains, “What I fear most is that the iron rod in the tall building will shift and drag me along, causing us to fall.”

He adds, “But I don't find this work dangerous; I've become an expert at it.”

We asked Issa what precautions he takes to keep himself safe. He mentioned that he wears a helmet, but we didn't see one with him when we met. He explained that he usually wears it but said, “I forgot my helmet at home today.”

A picture shared with us by Issa.

A picture shared with us by Issa.

There are no statistics available on the number of children who have lost their lives due to work, whether on construction sites or elsewhere. We posed this question to Jalaa Hamzawi, director of the Children with Diabetes Club and an advocate for children's issues. She explained that incidents of children falling from upper floors of buildings or being struck by falling stones are often reported, leading to severe injuries, including amputations of limbs or fingers.

“Children involved in hazardous work, particularly in industrial areas, face the risk of accidents such as a barrel exploding on them,” added Hamzawi, “Even children selling tissues on the streets are in danger, especially during rush hour, and could be run over.”

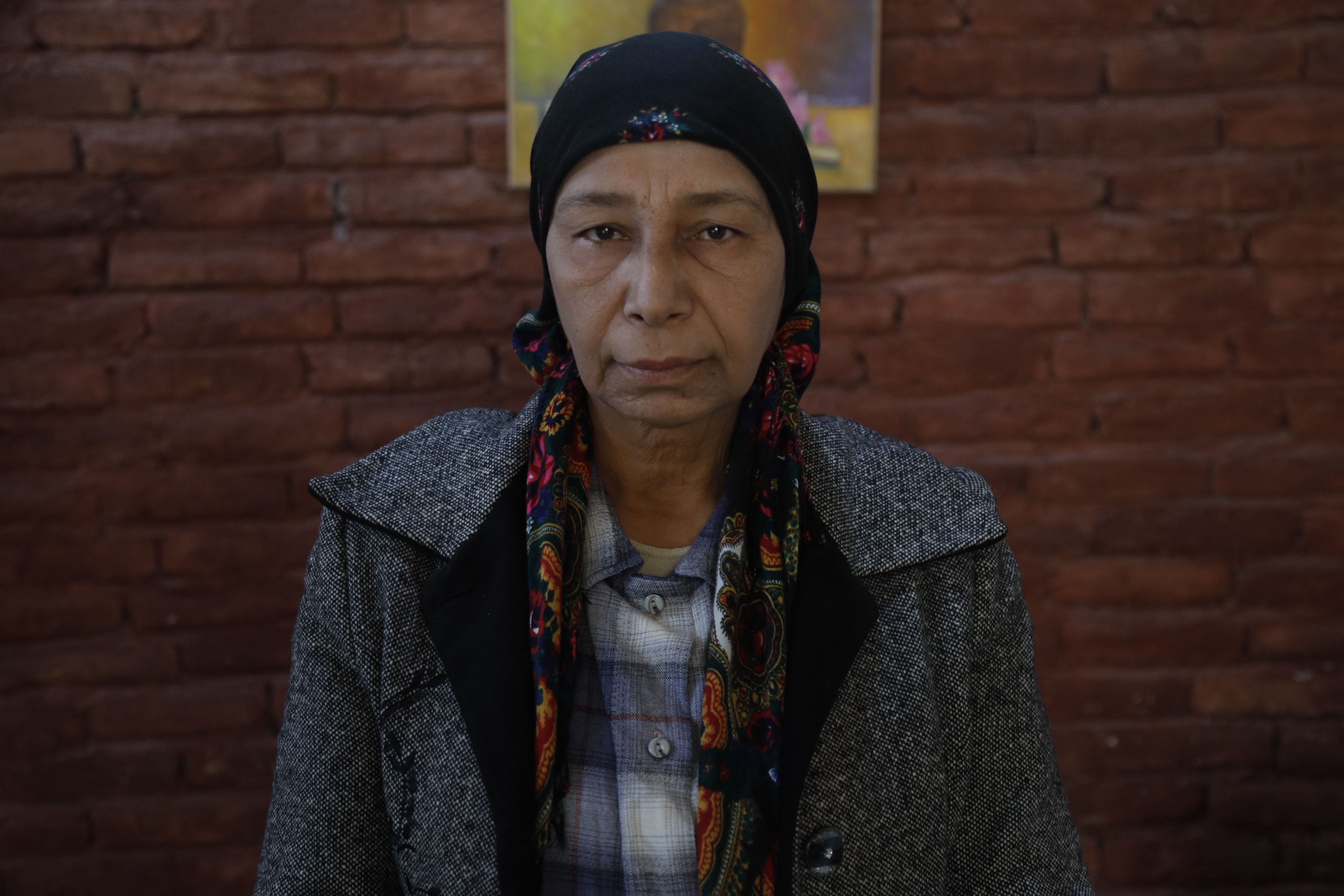

Jalaa Hamzawi

Jalaa Hamzawi

“All professions are dangerous for children, regardless of their nature or location, and none of them are suitable for the childhood of these young workers,” says Hamzawi.

She adds, “One incident that deeply affected me and is hard to forget involved a young child who was delivering an order on his bicycle. He fell into a large hole, resulting in a fracture of his spine and neck, which ultimately led to his complete paralysis. This situation is profoundly painful.”

In a previous survey conducted by Save the Children, approximately 80% of families in Raqqa reported resorting to desperate measures, such as purchasing food on credit and pulling their children out of school to work in order to meet basic needs.

Child Worker: Fast, Silent, and Underpaid

Issa wraps iron wire around his waist, gripping a cutter and a measuring tape in his hands—tools he has been using since he was ten years old to help build houses in north-eastern Syria.

Issa loves to sing. We heard him humming a tune as he measured and cut the iron. When we asked him to sing a bit for us, he was shy at first but eventually agreed. He has a lovely voice!

As we listened to him, Abu Ibrahim, the person in charge of the workshop, walked by. It was a perfect opportunity for us to talk with him about the children working here and the reasons behind their choice of this job.

Abu Ibrahim

Abu Ibrahim

“Most children began working after the war, each based on their living conditions and life circumstances,” says Abu Ibrahim. “The situation is different now than it was before. Some children have lost their fathers, and each one has unique circumstances that compelled them to work.”

Although Abu Ibrahim, a father of four, is against child labor in general and does not want his own children to work, he explains that the presence of these children in his workshop is “to help them financially,” as he sees it.

Children are more vulnerable than adults, and Abu Ibrahim recognizes this. He notes that there have been no serious accidents in his workshop, but he has heard about incidents in other places. “Children can get injured while carrying iron, or one might forget to watch where they’re going while playing and fall down the stairs, breaking a leg,” he explains. “However, the children here have not experienced any accidents.”

We asked him, “What sets Issa apart from the others?” He replied, “Issa is a child, and children don’t complain; they do what is asked of them quickly and directly.”

Regarding the wages paid to children, he explained that their earnings are lower than those of adult workers, justifying this by saying, “A child's productivity is not comparable to that of an adult, so their wages will be less.”

According to a World Bank report, Raqqa and other cities in north-eastern Syria have some of the highest poverty rates in the region. In 2022, poverty affected 69% of the population, or approximately 14.5 million Syrians. While extreme poverty was not prevalent before the conflict, it impacted more than one in four Syrians by 2022.

The United Nations previously reported that 90% of Syrians live below the poverty line, including Issa and his family.

At noon, Issa takes on the responsibility of bringing food for himself and his colleagues at the construction site, a task typically assigned to the younger workers. Today, he brought falafel patties, along with bread and tomatoes. They sliced the tomatoes and added them to the falafel in the bread before enjoying their meal together.

Before he brought us the food, Issa mentioned that this was the only time during their 11-hour workday when they could take a break. Even if he felt tired, there was no time to stop, as the meal break was their only opportunity to catch their breath.

Issa works approximately 66 hours a week, spread over six days, with Friday being his only day off. He earns a daily wage of between two and three dollars.

A simple comparison between what Issa earns for his work and the wages of construction workers in other countries highlights a significant disparity. It’s important to consider that the legal working age varies, with stricter laws regarding child labor in many nations.

For instance, in the United States, the average minimum wage for a construction worker is approximately $15 per hour. Working 8 hours a day, a construction worker can earn about $120 a day, which is 40 to 60 times more than what Issa makes.

In Europe, for example in Germany, a construction worker can earn between 12 and 20 euros an hour (approximately $13 to $22). Over an eight-hour workday, this amounts to between $104 and $176, which is about 58 times what Issa earns.

The lunch break is the only opportunity to rest.

Today, he brought them falafel patties with bread and tomatoes. They slice the tomatoes, added them to the falafel in the bread, and enjoyed their meal.

All that concerns Issa right now is finishing his work and returning home, as tomorrow is Friday, his only day off. On Fridays, he can meet up with his friends, play with them, and watch cartoons.

He always hopes for work to finish early so he can play, but that often doesn’t happen, especially since the journey back home is challenging. Many days, his father is unable to pick them up because he is working the land, forcing Issa and his brothers to rely on public transportation. This often results in a long return trip, with the sun completely setting by the time they arrive home.

Issa has friends who both work and attend school. Some of them he knows from his job, while others are from his neighborhood.

The closest friend to Issa is Sami, who gave him a ring. Sami also works alongside Issa in construction and does not attend school like he does.

In the area, most parents believe the quality of education is poor, leading them to prefer sending their children to work and learn a trade that will be more beneficial. This preference is particularly influenced by the fact that over 80% of the schools remain in ruins.

Across Syria, an estimated 2.4 million children aged 5 to 17 are out of school, which accounts for nearly half of the approximately 5.52 million children of school age.

One in three schools in Syria is no longer serving its educational purpose, having been destroyed, damaged, or repurposed to shelter displaced families or for military use. The limited number of rehabilitated schools significantly hampers children's access to education, resulting in overcrowded classrooms. Additionally, tens of thousands of teachers and education workers have fled the country, exacerbating the crisis in the educational sector.

Rich People Mock My Children's Work, and It Hurts Me Deeply

After a long day of work, Issa returned home only to find that his father was still at the farm, where he had spent his own day working.

Issa took off his work clothes and took a shower before settling down to watch Spacetoon, eagerly awaiting his father's return so they could all share dinner together. He cherished those family moments.

This little boy would go to bed at eight o'clock at night, as his tired body could no longer endure the strain of the long day.

When his father returned home, he shared his past experiences in the iron industry, describing the harsh conditions he faced. He explained that while his sons now work in this field, he had to stop due to the severe physical toll it took on him. Unable to carry heavy weights any longer, he transitioned to agriculture, which is less strenuous and allows him to continue earning a living.

For him, if financial circumstances were better, he wouldn’t have to send his children to work. He expressed concern that the younger ones might be restless about it, while the older ones seemed more accepting. “I wish I could provide a better life for them, away from working in difficult conditions,” says Abdul Razzaq, Issa’s father.

“We all work to secure our livelihood because the financial situation in the region is extremely challenging,” he added.

From time to time, Issa's father faces criticism from those he considers financially better off, who claim they would never allow their children to work as he does. “This hurts me a lot,” Abdul Razzaq says. “Everyone has their own circumstances.”

Even though child labor is illegal in Syria, enforcing this law remains a challenge due to the ongoing conflict and economic instability.

Syrian labor laws stipulate a minimum working age of 15 for non-hazardous jobs and 18 for hazardous work, such as construction. However, due to high poverty rates, many families depend on their children's income, leading to limited enforcement of these laws.

Abdul Razzaq expressed his lack of awareness regarding the legal implications of child labor, stating, “I don’t know if what we’re doing is against the law, but I am acutely aware of its dangers and feel constant fear for my children.”

He recalled an incident when a child welfare organization visited the workshop and filmed the children at work. “They told us these children shouldn't be working here and promised to return to check on their cases, but we never saw them again,” he added.

Issa's father hopes for an improvement in their financial situation that would allow his children to stop working, though he feels pessimistic about the possibility of this happening.

However, Issa dreams of leaving the construction field behind and pursuing his aspiration of opening a bakery to sell cakes and biscuits. He also envisions building a cozy home for his family, where they can feel secure and at peace.