Abandoned Children

Foster Care in Northern Syria Amidst the War Years

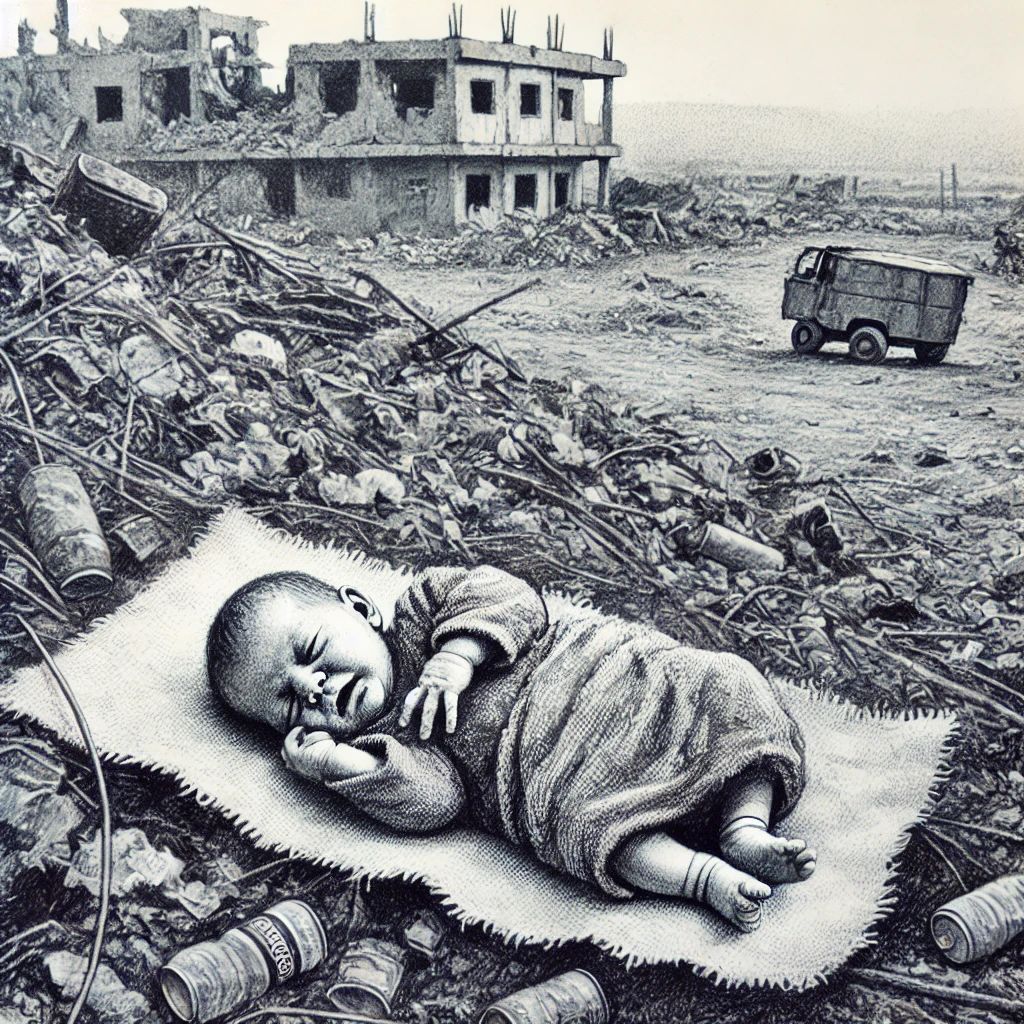

Receiving a phone call about a newborn abandoned in a garbage bin next to the child protection center where you work is not just an isolated incident—it's a chilling reminder of the urgency and depth of the crisis. Such moments demand immediate, unwavering action to save a child's life. For Manal*, this is one of many heart-wrenching scenarios she has encountered in her years of working with abandoned children.

It was nearly midnight on a bitterly cold night, as Manal, a humanitarian worker since 2015, recalls. She and her team had to act quickly, knowing that the newborn would not survive for much longer. "It seemed as though the person who abandoned this child was sending us a message," she tells Tinyhand. "If you don’t take care of him, let him die here in the trash bin. No problem."

This case was one of many that Manal has followed during her work with a humanitarian organization, where she managed the care of abandoned children in northwestern Syria. Manal explains that most of these children were the result of pregnancies from young girls who had been raped and were unwilling to keep the child. "The ages of these girls ranged between 15 and 16 years," she adds.

Girls were not the only victims of rape, Manal explains. She also worked with older women, saying, “The victims of sexual violence were not exclusive to girls.”

We met Manal during our investigation into the issue of abandoned children in northwest Syria. These children are often left in the most unexpected place, outside hospitals, mosques, streets, or police stations. Some are taken in by child protection teams, while others end up in orphanages. However, many remain unknown, their stories lost to time and circumstance.

All names in this investigative report have been changed to protect the safety and security of those involved and to ensure the identities of the foster families who have taken in some of these children remain confidential. Confidentiality is a fundamental principle in the success of this mission, as safeguarding the identities of both the children and the families providing care is critical, particularly in regions affected by ongoing conflict and instability.

The interviews in this investigation were conducted before the fall of the regime.

Victims of Poverty, Victims of Rape

Working in the field of child protection for those abandoned due to rape is a perilous job, especially when the parties involved fail to uphold confidentiality.

Manal explains that one of the biggest challenges they face is the conflict between workers in gender-based violence and the medical sector. Some people in this field break confidentiality by treating survivors as patients, not as victims, and they refuse to keep things private when dealing with local authorities.

Despite their best efforts, Manal and her team have faced danger several times. She remembers one case with a rape survivor who did not want to keep her baby. They had to stay with her until the baby was born, then leave the child at the hospital to be found later and look for a foster family. However, the hospital’s security cameras caught them when the director complained that they had left the baby there.

While all of Manal’s cases involved children born from rape, Jamil*, a humanitarian worker with more than ten years of experience, deals with cases of children abandoned because of poverty.

Why Children Are Abandoned?

Many newborns in these areas are abandoned due to unwanted pregnancies, like those from rape or illegal relationships. Mothers often leave their babies out of fear of social stigma or because they can't care for them, and there is no social or legal protection for them. In other cases, extreme poverty leads families to leave their babies in hospitals or other safe places, hoping someone will take care of them.

Saving a Child from an Unknown Fate

Jamil* started working in child protection in 2016 when he joined a team that provided emotional and social support to children in shelters. Over time, he moved to fieldwork, where he began helping children who were abandoned or lost their families.

“The first case I worked on was in 2019. It was a newborn baby found outside a hospital in Idlib,” Jamil recalls. “At that time, we didn’t have enough experience or clear rules, but we worked to create ways to protect these children by finding them foster families.”

The Foster Care System: Finding a Safe Home

One of the biggest challenges was finding families who could take care of these children in a safe and stable home. “We carefully check the families to make sure they can provide good care. We also get permission from the legal and religious authorities to make sure everything is done correctly,” Jamil explains.

For the baby found in Idlib, the child received medical care and was temporarily placed with a nurse until a suitable family was found. “We looked for a family with a stable environment and the ability to care for the child. We chose a couple who had no children and were eager to adopt the baby.”

After signing an agreement to ensure the child would not be mistreated and would not be treated as a biological child of the family, the baby was officially handed over to the selected family. Today, after four years, the child lives a normal life and attends kindergarten.

Legal and Social Challenges

Working in this field comes with many legal and social challenges. One of the biggest problems is that there is no civil registry for abandoned children in northern Syria, making it very difficult to register these children officially.

“We are asking the authorities to create a special registry for these children to ensure they get their rights, like education and healthcare. But there is still no law to help them,” Jamil says.

On top of that, teams working in child protection face security challenges, as the situation can change quickly, making their work harder. “Sometimes, social pressures stop us from helping or make it difficult to move children from unsafe places to better homes,” Jamil explains.

Despite these challenges, Jamil and his team keep working hard to save as many children as possible. “Every child we help is a step toward a better future. We can’t change everything, but we try to do our part,” he concludes. “The most important thing is that everyone involved must understand that these children are not at fault.”

The Syrian Center for Truth and Justice has documented about 100 children being abandoned between 2021 and 2022 in different areas of Syria.

Serious Threats That Could Lead to a "Prostitution Case"

Working in child protection comes with significant risks, as activists navigate not only complex cases but also societal resistance to addressing such sensitive issues. The absence of a unified regulatory body for specialized organizations often leads to fragmented efforts, leaving children even more vulnerable to neglect and abuse.

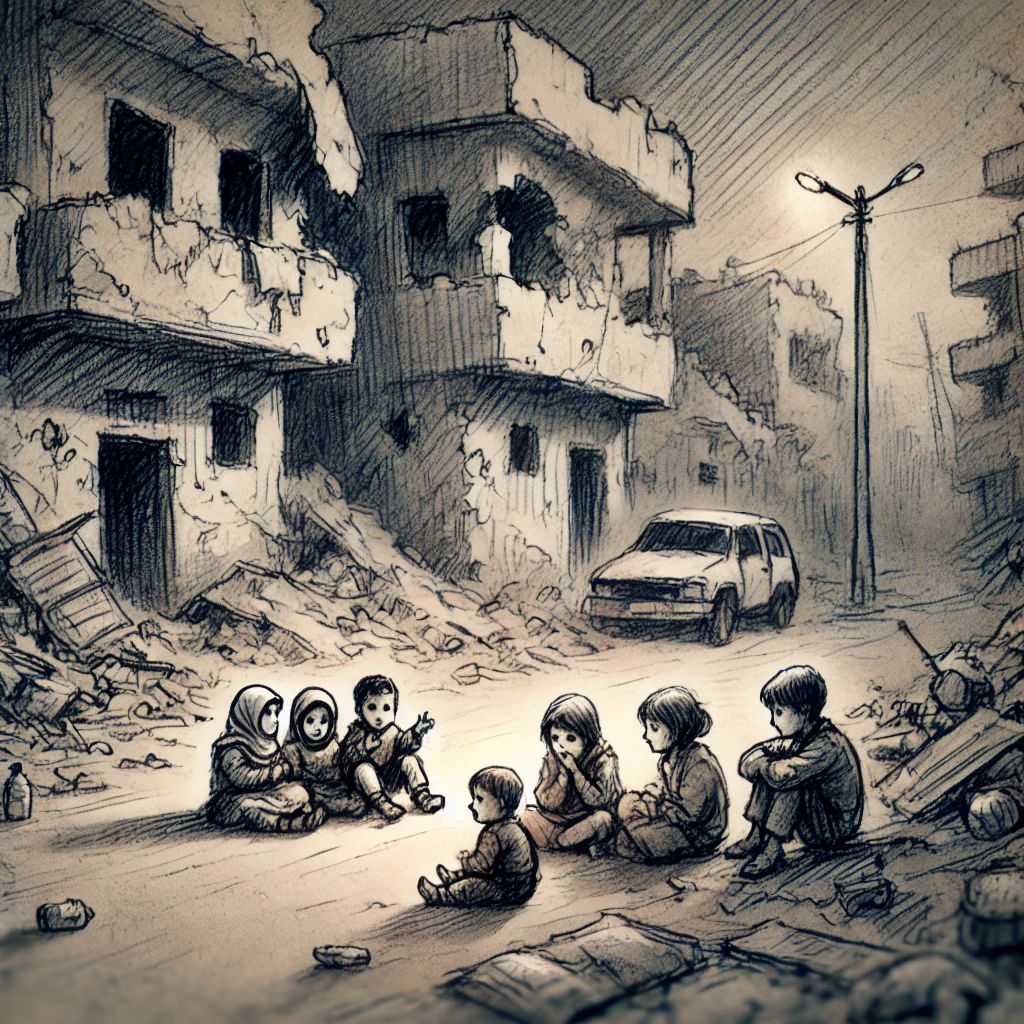

Mona*, 41, has worked in the humanitarian field since 2013, beginning her career in Aleppo. Over the years, she has witnessed heartbreaking cases, including children separated from their families by sniper attacks at crossing points.

One case she handled involved a mother and her three children who were caught in an airstrike while fleeing Aleppo. The mother did not survive, but her children—a girl and two boys—were rescued and taken to a hospital in Aleppo in 2016. Later, they were relocated to opposition-controlled areas.

The best solution was to reunite them with their father, but Mona later discovered that he was struggling with drug addiction and exploiting the children. She tried to support them by providing essentials like stationery and bedding, but the abuse continue, he would beat them or throw them out of the house. Having already witnessed their mother’s death, the children were left in an unbearable situation.

Mona is not alone in facing significant challenges while working with abandoned children. Every person we met had a different, often dangerous experience, and perhaps one of the most perilous was Khaled’s*.

Khaled faced legal and personal risks when he was pursued legally after taking a child found at a hospital, whose mother refused to take him. He was accused of being the child’s father and nearly faced a major prostitution case. However, the situation was resolved after confirming his trusted humanitarian work.

Khaled, who has personally handled 17 cases of abandoned children, highlighted the widespread legal and personal violations in this field. He noted that society resists proper recognition of women's and children's rights, while the lack of a unified judicial system allows these cases to be exploited.

Hope for a Better Life for These Children

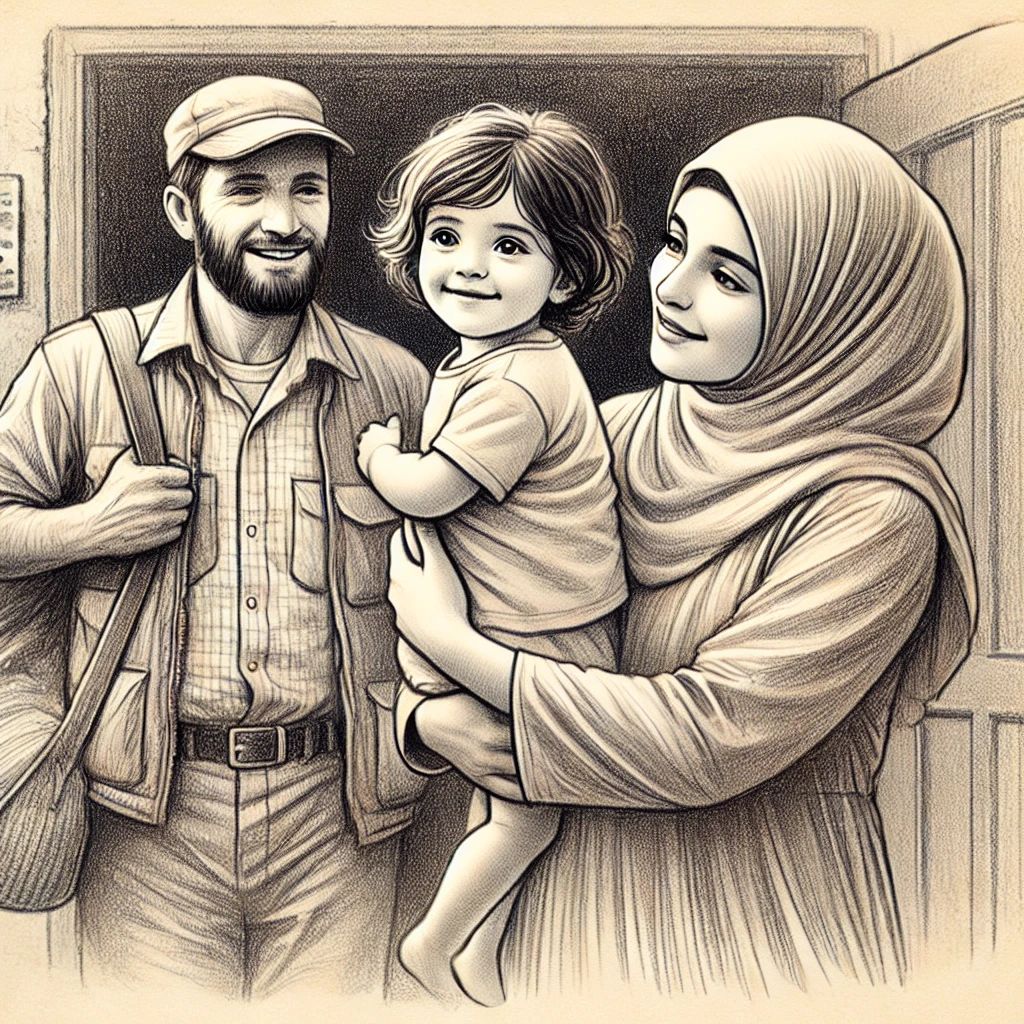

Amid harsh humanitarian conditions, the stories of Basma and Jad reflect the power of love and sacrifice. Basma, a baby no older than nine months, was placed in the care of Jamal and Amal in Ariha, Idlib, after a thorough evaluation by a child protection center. Since then, she has transformed their lives, becoming, in her mother’s words, “an indescribable source of happiness.” Amal’s greatest priority is ensuring Basma receives the best care and education, hoping she will excel academically. Despite financial hardships, her sole focus remains on the child’s well-being, never on herself.

Jad, now two years old, has a story just as heartwarming. His mother had longed for a child for 22 years, and his arrival filled her life with joy. The moment she held him for the first time was deeply emotional, especially as she tended to his needs providing him with clothes, milk, and medicine pouring all her love into his care.

Jad’s mother dreams of giving him the best education and a bright future, but she lives in fear that he might be taken from her if his biological parents are found. Her greatest hope is that he grows up with a sense of security, free from the weight of his past.

Despite their hardships, both families chose to give these children hope, care, and a chance at a better life embracing them with love while knowing nothing about their biological families.

These families have also made the decision to reveal the truth about their pasts to their children at the appropriate time, in order to prevent feelings of anxiety or regret as they grow older. Basma's mother hopes that the truth will play a role in shaping her daughter's strong character, free from any psychological burdens. Similarly, Jad's mother plans to share the truth with him when he turns ten.

Where Does the Law Stand on Abandoned Children?

Syrian law remains fractured on the issue of abandoned children. In 2032, Bashar al-Assad introduced Legislative Decree No. 2, establishing Melody of Life Homes—the sole legal authority overseeing the care and protection of children of unknown parentage across Syria. However, in opposition-held areas before the regime’s fall, earlier legal frameworks continued to govern these cases.

Syrian lawyer Rahada Al-Abdoush explains to Tinyhand that "a child born outside of marriage is attributed to the mother, not the father, and often the mother abandons the child, requiring state intervention to provide care." This is based on Legislative Decree No. 107 of 1970, which defines an unknown parentage child as "a newborn found without the knowledge of its parents." Article 18 of the decree further outlines the care provided to these children "Children of unknown parentage who have no legal guardian to support them.

Children who lose their way and cannot find their families due to age, mental disabilities, or being deaf and mute, and whose families make no effort to recover them.

In the absence of relevant government bodies, such as the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour in opposition-controlled areas, humanitarian workers have taken on the responsibility of finding alternative families for these children, ensuring their care, education, and preparation for independent lives.

Despite social and local challenges, these workers have followed Syrian legal standards when searching for foster families, which require that both parents be between 30 and 60 years old, with exceptions made if deemed in the child’s best interest. They also ensure a suitable social, economic, educational, and health environment.

Al-Abdoush concludes: "After the regime's fall, it is expected that any decrees issued under Assad's rule regarding children of unknown parentage will be reviewed or canceled to unify laws across all Syrian regions.