The Plight Of Yezidi Child Survivors Of Isis

“I will never forget what happened to me. It is a part of me, like a mark. It’s there forever. It’s the worst thing that can happen to any human, the most degrading. When I came back... no one gave me any support, no one put out their hand. What I was looking for is just someone to care about me, some support, to tell me, ‘I am here for you.’ Someone to put their hands on my shoulders and say everything will be ok... This is what I have been looking for, and I have never found it.” Sahir, who was forcibly recruited by IS at the age of 15.

Between 2014 and 2017 the armed group calling itself the Islamic State (IS) committed war crimes and crimes against humanity against the Yezidi community in Iraq. A UN Commission of Inquiry concluded in 2015 that IS committed acts against the Yezidi community that amount to genocide. Yezidi children were abducted by IS and enslaved, tortured, forced to fight, raped and subjected to other egregious human rights violations.

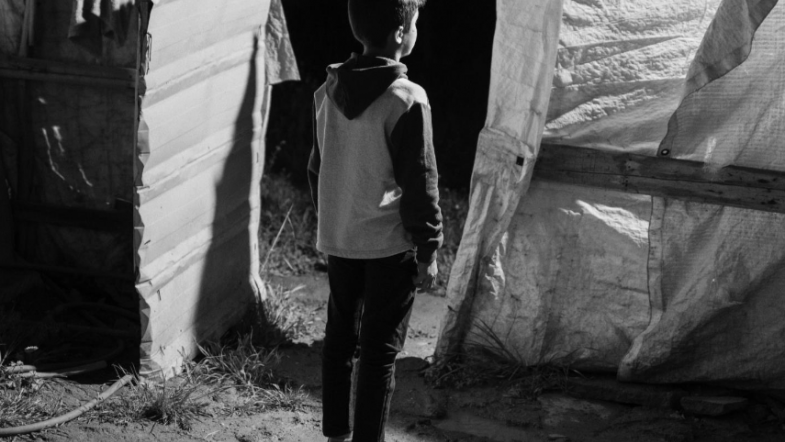

While thousands of children were killed or abducted, hundreds survived and returned to their families in Iraq. Yet their homecomings have not marked the end of their suffering.

Upon returning to their families and community, these child survivors face significant challenges. Their physical health is often severely compromised; many experience mental health conditions; they sometimes cannot speak or even understand the dialect of Kurdish spoken by their families; many are unable to re- enrol in school after missing several years; and they face barriers to obtaining new or replacement civil documents, which in Iraq are essential to exercising basic rights and receiving key benefits.

Yezidi women who were abducted by IS and gave birth to children as a result of sexual violence likewise face difficult challenges. Many of them have been forced to separate from their children due to religious and societal pressures and are in a state of severe mental anguish.

Under international law, all children have the rights to health, education, legal identity and family unity without discrimination. Children who are victims of violations of human rights and international humanitarian law are entitled to full reparation. Amnesty International’s research shows that the authorities of the Iraqi central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) are falling short of their obligations to respect and guarantee these rights and ensure reparation for Yezidi child survivors. Without a drastic shift in policy and priorities by national authorities, with the assistance of the international community, these children will continue to face the legacy of IS’s crimes without the support they need and to which they are entitled.

CHALLENGES FOR CHILD SURVIVORS

Many child survivors return to their families having been starved, tortured or forced to endure or participate in hostilities. In many cases, these experiences have a major impact on their health. While some children return with treatable conditions such as anaemia or scabies, others have debilitating, long-term injuries, illnesses or conditions. As a result of their involvement in fighting, boys who were forcibly recruited by IS are especially likely to suffer from serious health conditions and physical impairments, such as lost arms or legs during fighting. Girl survivors of rape and other sexual violence suffer unique health issues, including traumatic fistulas; scarring; and difficulties conceiving, during pregnancy or giving birth to a child.

The majority of child survivors and caregivers interviewed, as well as many humanitarian workers, said that the health needs of child survivors are not currently being met, particularly with regard to long-term, serious health conditions and injuries. The case of Rayan, who was forcibly recruited by IS at the age of 15, is typical.

“I was guarding the front lines [and] I was injured by an artillery [shell],” he explained. “My right leg got a big piece of shrapnel in it, in my hamstring... This shrapnel is just sitting in my body. It’s almost three years since I am back, and there is nothing [no treatment].”

Child survivors who return from captivity have endured unimaginable trauma. Almost every caregiver interviewed said that the mental health of the child survivor they looked after had been affected by their time in captivity.

While each child’s situation is unique, mental health experts have detected some patterns, finding that the most common conditions experienced by Yezidi child survivors include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression.

Symptoms and behaviours often displayed by child survivors include aggression, hyperactivity, flashbacks, recurrent nightmares, bed-wetting, withdrawal from social situations and severe mood swings.

Every humanitarian actor interviewed for this report told Amnesty International that the psychosocial services and programmes currently available to Yezidi child survivors fall short of meeting these children’s rights and needs.

As a case worker from Yazda, a humanitarian organization that provides assistance to the Yezidi community, said, “It’s true that some organizations are working on this, and we are doing what we can, but much, much more is needed by these children.” Humanitarian workers and mental health professionals also highlighted the importance of improving the quality of existing services, and transitioning away from the current short-term approach taken by many organizations to a long-term, holistic approach, ideally coordinated under one over-arching strategy.

Humanitarian workers, mental health professionals and caregivers often spoke of particular challenges for two groups of child survivors: former child soldiers and girls who were subjected to sexual violence, among many other human rights abuses.

Yezidi boys who were forcibly recruited by IS often faced months or even years of intense propaganda, indoctrination and military training, deliberately intended to erase their former identities, language, history, culture and even names.

Upon returning from captivity, their relationships with their family members and community can be fraught with tension, at times rising to threats and harassment against the boys. More than half of the 14 former child soldiers interviewed for this report said they had not received any form of support – whether psychosocial, health, financial or otherwise – after their return.

CHALLENGES FOR FAMILY MEMBERS OF CHILD SURVIVORS

Parents and other family members caring for children who have returned after IS captivity told Amnesty International that they were struggling to meet the needs of these children.

Many Yezidi families are impoverished – in part, in many instances, because they were forced to pay thousands or tens of thousands of dollars as ransom to secure the release of these children and other family members from IS captivity.

Humanitarian workers also noted the absence of programmes to educate parents and other caregivers about what their children are going through, or on how to help their children adjust after they return from captivity.

In light of the many challenges they face in reintegrating and caring for child survivors, several caregivers expressed despair at their situations. For instance, Arzan, whose 14-year-old son she said has fits of rage, hyperactivity and aggressive tendencies, told Amnesty International: “At the beginning, I was dreaming of him coming back to me. Then when he came back, I couldn’t have one normal meal with him, not one normal moment... It cannot get worse than this.”

The situation of Yezidi women who gave birth to children as a result of sexual violence by IS requires the urgent attention of the national authorities and the international community. As a result of IS’s policies of systematic rape and sexual enslavement, Yezidi women gave birth to hundreds of children during their captivity.

Due to many factors, including the stance of the Yezidi Supreme Spiritual Council and the current legal framework of Iraq, which mandates that any child of a Muslim or “unknown” father be registered as Muslim, these children have been largely denied a place within the Yezidi community. These women have therefore been forced into either keeping their children but giving up their families and community, or giving up their children but reuniting with their families and community.

According to civil society activists and staff members of local and international humanitarian organizations, the Yezidi community’s response to this issue has been mixed.

While many in the community strictly oppose accepting children born of sexual violence, others would be willing to accept them, especially if given a positive signal by religious authorities.

Still others feel compassion and sympathy for these women and children and believe they should be supported, but given the edicts of Yezidism, cannot see a place for them within the community.

Many of these women are in desperate situations, in some cases experiencing severe mental anguish after being forced to separate from their children, and in others, remaining in IDP camps or with IS captors to avoid giving up their children.

Several such women interviewed by Amnesty International said they were pressured, coerced and even deceived into leaving their children behind by family members or by individuals or groups who work to reunite captured Yezidi women and children with their families.

They also said they were falsely assured that they would be able to visit or reunite with their children at a later stage.

Hanan, a 24-year-old survivor of IS captivity, told Amnesty International: “My uncle was promising on his honour and dignity that whenever I wanted, I would visit my daughter. I went to the orphanage to leave her. When I left her, I was shouting at them, ‘Don’t give my daughter to anyone.

I will come back every week, every month – this is temporary!’ When I saw my uncle, his first words were, ‘Forget your daughter.’”

Sana, a 22-year-old survivor of IS captivity, took her daughter with her to an IDP camp, but was forced to give her up after she received repeated death threats. She said: “I took her to the office [of a local NGO], and they said to leave my daughter... They said: ‘We will be the father and the mother for her.’ In that moment, it felt like my backbone broke. My whole body collapsed.”

All of the five women interviewed who were separated from their children said they did not have access to their children, or any way of communicating with or receiving news about them.

They also said that they were unable to speak with their families or community about their desire to reunite with their children, due to fears for their own safety.

The trauma these women experience from being separated from their children is therefore compounded by further distress: many were forced to leave their children or were deceived into giving them up; they have no means of contacting them; they have no news of their welfare; they often cannot share feelings of anguish with others in their families or community; they have no psychosocial support on this issue; and they have no help in reuniting with their children and see little prospect of this ever happening.

Several of the women interviewed said they had attempted to commit suicide. Some had tried to do so more than once. All pleaded for the international community and national authorities to act quickly, as they found their current situations unbearable. Janan, a 22-year-old survivor of IS captivity, told Amnesty International:

“I want to tell my community and everyone in the world, please accept us, and accept our children. We are survivors of IS. Imagine the pain we have seen... I didn’t want to have a baby from these people. I was forced to have a son. I would never ask to be reunited with his father, but I need to be reunited with my son.”